Lab 12: Human Renal Function

Acknowledgements

Starting at dinner the night before lab, please attempt to consume a normal amount of liquid, and try not to intake unusual amounts of caffeine or (ahem) alcohol. Record what you eat and drink starting at dinner the night before your lab.

Do not drink or eat anything but water during the 2-hour period before lab. (have lunch before 11:30 AM for a 1:30 PM lab, or 12:30pm for a 2:30 PM lab). You may drink as much water as you wish.

Urinate one hour before coming to lab (note the time). Do not urinate again until the first collection at the beginning of laboratory.

If you have circulatory problems, poor kidney function or have any medical condition related to diet, do not volunteer as a subject for this experiment.

- Read the lab manual below.

- Write the [Prelab] in your lab notebook. Please DO NOT copy the lab manual word for word. Your task is to summarize the important points that are useful for developing hypotheses for this experiment.

- This week, draft hypotheses for each experiment.

- To obtain feedback from your TAs, for the prelab please have the hypotheses, figuring out how many ideas you have to cover, and writing a topic sentence for each paragraph:

- Motivating question/umbrella idea

- introduce mechanism 1

- introduce mechanism 2

- …

- end with a paragraph of your hypotheses

- For the methods, outline:

- subjects

- equipment

- experimental treatments (be sure to note what variables are changing) and controls or comparisons

- analysis

- Do Quiz on Laulima (open 24 hrs before lab).

- Please bring a laptop with you to lab, if possible, to analyze your experimental results.

Summary

In this lab, we will examine renal responses to the intake of various solutions in the most convenient experimental animals available. Changes in urine composition will be analyzed in humans after the consumption of solutions hypo-, iso-, and hyper-osmotic to extracellular fluid, as well as basic, acidic, and sugary solutions.

Background

The mammalian kidneys play a major role in homeostasis involving both osmoregulation (the balance of water and electrolytes) as well as waste excretion. The are the primary organs involved in regulating the ionic content, pH, and osmotic pressure of the blood.

Kidneys filter the blood by glomerular filtration and form urine through tubular reabsorption and tubular secretion. Small molecules including water and small molecules filter out of the glomeruli (like through a sieve). As the filtrate passes through the nephrons some biologically important substances, such as sodium, calcium, glucose, and amino acids, are reabsorbed, whereas other substances, such as potassium and hydrogen ions which will become waste products, are secreted into the collecting duct.

Glucose is the universal energy molecule. The kidneys resorb glucose with such high efficeincy that sugar is typically not found in the urine. However, there is a limit. If the blood sugar level exceeds a value known as the renal threshold, the kidneys cannot reabsorb all the glucose in the glomerular filtrate and some sugar will appear in the urine. Many substances are normally reabsorbed in the kidney tubules, but most are not reabsorbed as completely as sugar.

Mammals do not have a salt gland, therefore the only mechanism for excretion of excess salts is dilution through the kidneys. Humans have the ability to concentrate the urine somewhat, to about 4x that of the plasma concentration, or about 1400 mOsm.

A massive amount of water (up to 99% of the glomerular filtrate) is reabsorbed both in the nephrons and collecting ducts of the kidneys. Therefore, the volume of urine excreted may represent less than 1% of the volume of glomerular filtrate. The volume of water is adjusted depending on the hydration level of the mammal.

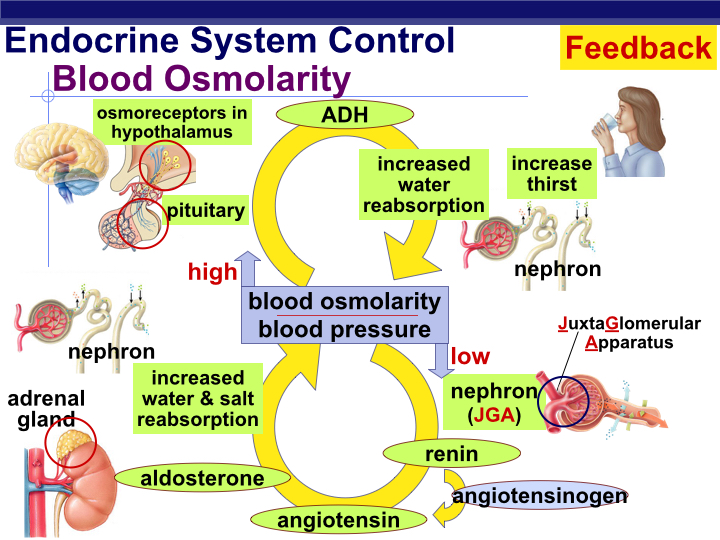

Water resorption is enhanced by a hormone called antidiuretic hormone (ADH), which is released from the posterior pituitary. Changes in fluid intake or fluid volume (loss of fluid from the body) can change the rate of ADH release and therefore the rate water excretion and urine production (Figure 1).

Human beings, like other osmoregulators, maintain osmotic and ionic conditions through homeostatic mechanisms. When a large volume of water is lost from the bodyʻs interstitial fluid (via dehydration or other mechanisms), plasma osmolarity will increase, be detected, and corrected mainly through feedback regulation. The control of water retention by the human kidney is a well-known example of physiological feedback control.

Changes in plasma osmolarity are sensed by osmotically-sensitive neurons located in the hypothalamus (Figure 1). Increased plasma osmolarity causes these neurons to increase their rate of signal transmission to the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland, from which ADH (antidiuretic hormone) is releasted into the circulatory system. ADH travels through the blood and eventually finds its way to the epithelial cells that make up the walls of the kidney’s collecting ducts, where it causes the walls of the collecting duct to become more permeable to water. Water then flows from the collecting duct back into the kidney, so that the body retains more water and urine concentration increases (highly concentrated urine is very yellow in appearance).

Water conserved by ADH re-enters the circulatory system through the capillary network that surrounds the entire tubular system of the kidney. Water resorbtion will decrease plasma osmolarity (i.e., it dilutes solute concentrations in the blood). Eventually, the lower plasma osmolarity is sensed by the neurons in the hypothalamus and the firing rate of these cells decrease, resulting in less pituitary stimluation, reducing the secretion of ADH. The collecting duct becomes less permeable to water, so that more water flows out of the collecting duct, producing a more dilute urine.

Another feedback mechanism involves the synthesis and release of Aldosterone, a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal cortex in response to increased extracellular potassium (low extracellular Na+). Release of Aldosterone results in sodium reabsorbtion in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) and the collecting ducts of the mammalian kidney. As sodium is reabsorbed from the kidney tubule, extracellular osmolarity increases (sodium is the main extracellular ion in human interstitial fluid). Eventually, extracellular osmolarity reaches a value that inhibits further release of Aldosterone. In the absence of Aldosterone, sodium is permitted to pass through the DCT/collecting ducts and finally is excreted in the urine. Osmoregulation via the kidneys are the result of a elegant anatomical design coupled with a beautiful system of feedback regulation.

The kidneys are extremely hard-working organs. Humans are born with all of the glomeruli that they will ever have, and they do not regenerate if they are damaged. With greater demand on the kidneys, individual glomeruli will enlarge in an attempt to compensate for the load. With serious renal disease the only options are kidney dialysis (which is not an ideal solution) or a kidney transplant for otherwise healthy patients who are lucky enough to have a donor. Unfortunately, artifical kidneys are not yet available although it is an active area of research. Therefore it is important to maintain renal health.

Today’s lab exercise is designed to illustrate human kidney function. You will measure the output of your own urine and (with data pooled from other class members) determine the effect of experimental intake of a range of solutions on urine physical, chemical, and biological characteristics.

Equipment

- Drinking cups

- Graduated urine specimen cups

- Test tubes and racks

- Wash bottles

- Combur Test chemstrip Urinalysis Tool

- pipettes

- Cl- determination reagents.

Procedure

Analysis of Urine

We will measure the urine volume (using a graduated flask), chloride ion content, and the chemical/biological composition of urine using a chemstrip urinalysis test product (used for initial clinical diagnostic screening). The chemstrip tests for a number of different properties of urine, including specific gravity, pH, infection, immune system activity, insulin imbalance, blood chemistry, and liver function.

Here is a detailed description of what the chemstrip measures:

Specific Gravity: The specific gravity test permits the determination of urine specific gravity between 1.000 and 1.030. For increased accuracy, 0.005 maybe added to readings from urine with pH equal to or greater than 6.5. Elevated specific gravity readings may be obtained in the presence of moderate quantities (1‑7.5 g/L) of protein. The specific gravity of urine is a measurement of the density of urine; the relative proportions of dissolved solids in relationship to the total volume of the specimen. It reflects how concentrated or diluted a sample may be. Water has a specific gravity of 1.000. Urine will always have a value greater than 1.000 depending upon the amount of dissolved substances (salts, minerals, etc.) that may be present. Very dilute urine has a low specific gravity value and very concentrated urine has a high value. Specific gravity measures the ability of the kidneys to concentrate or dilute urine depending on fluctuating conditions. Normal range 1.005 - 1.030, average range 1.010 - 1.025. Low specific gravity is associated with conditions like diabetes insipidus, excessive water intake, diuretic use or chronic renal failure.

Glucose: The glucose reagent panel is specific for glucose. The reactivity of the glucose test decreases as the Specific Gravity of the urine increases. Small amounts of glucose may normally be excreted by the kidneys, these amounts are usually below the sensitivity range of this test but on occasion may produce a color between the ‘Negative’ and the 100/5 color block and may be interpreted by the observer as positive. Glycosuria is the condition of glucose in urine. Normally the filtered glucose is reabsorbed by the renal tubules and returned to the blood by carrier molecules. If blood glucose levels exceed renal threshold levels, the un-transported glucose will spill over into the urine. Main cause: diabetes mellitus

Ketones: This test reacts with acetoacetic acid in urine. It does not react with acetone or β−hydroxybutyric acid. Some high specific gravity/low pH urines may give reactions up to and including ‘Trace’. Normal urine specimens usually yield negative results with this reagent. False positive results (trace or less) may occur with highly pigmented urine specimens. Ketone bodies such as acetoacetic acid, β−hydroxybutyric acid, and acetone can appear in urine in small amounts. These intermediate by-products are associated with the breakdown of fat. Causes: diabetes mellitus, starvation, diarrhea.

Blood: Blood is often found in the urine of menstruating females. This test is equally sensitive to hemoglobin and myoglobin. The sensitivity of this test may be reduced in urines with high specific gravity. False positives reactions can be caused by certain oxidizing contaminants such as hypochlorite and microbial peroxidase associated with urinary ’tract infection. Hemoglobinuria is the presence of hemoglobin in the urine. Causes: hemolytic anemia, blood transfusion reactions, massive bums, renal disease Hematuria is the presence of intact erythrocytes and is almost always pathological. Causes: kidney stones, tumors, glomerulonephritis, physical trauma.

pH: The pH test area measures pH values within the range of 5 - 8.5. Average is 6.0, slightly acidic. High protein diets increase acidity. Vegetarian diets increase alkalinity. Bacterial infections also increase alkalinity.

Protein: The reagent area is more sensitive to albumin than to globulins, hemoglobin, and mucoprotein. A ‘Negative’ result does not rule out the presence of other proteins. Normally no protein is detectable in urine by conventional methods, although a minute amount is excreted by the normal kidney. A color matching any block greater than ‘Trace’ indicates significant proteinuria. For urine of high specific gravity, the test area may most closely match the ‘Trace’ color block even though only normal concentrations of protein are present. False positive results may be obtained with highly alkaline urines (pH >8.5). Albumin is normally too large to pass through glomerulus tissue, therefore elevated results Indicate abnormal increased permeability of the glomerulus membrane. Non-pathological causes are: pregnancy, physical exertion, increased protein consumption. Pathological causes are: glomerulonephritis bacterial toxins, chemical poisons.

Nitrite: This test depends upon the conversion of nitrate (derived from the diet) to nitrite by the action of principally gram-negative bacteria in the urine. The test is specific for nitrite and will not react with any other substance normally excreted in urine. Pink spots or pink edges should not be interpreted as a positive result. Any degree of uniform pink color development should be interpreted as a positive nitrite test suggesting the presence of 100,000 or more organisms per ml, but color development is not proportional to the number of bacteria present. A negative result does not in itself prove that there is no significant bacteriuria. Negatives may occur when urinary tract infections are caused by organism which do not contain reductase to convert nitrate to nitrite; when urine has not been retained in the bladder long enough (4 hours or more) for reduction of nitrate to occur; or when dietary nitrate is absent, even if organisms containing reductase are present and the bladder incubation is ample. Sensitivity of the nitrite test is reduced for urines with a high specific gravity. High abnormal readings indicate the presence of bacteria. Causes: urinary tract infection.

Leucocytes: Normal urine specimens generally yield negative results; positive results of small (+) or greater are clinically significant. Individually observed ‘Trace’ results may be of questionable clinical significance; however, ‘Trace’ results observed repeatedly may be clinically significant. ‘Positive’ results may occasionally be found with random specimens from females due to contamination of the specimen by vaginal discharge. Elevated glucose concentrations or high specific gravity may cause decreased test results. The presence of leukocytes in urine is referred to as pyuria (pus in the urine). Causes: urinary tract infection.

Urobilinogen: This test area will detect urobilinogen (a bile pigment derived from hemoglobin breakdown) in concentrations as low as 3 mIU/L in urine. The majority of this substance is excreted in the stool, but small amounts are reabsorbed into the blood from the intestines and then excreted into the urine. Causes: hemolytic anemia, liver diseases.

Bilirubin: Normally no bilirubin is detected in urine. Bilirubin comes from the breakdown of hemoglobin in red blood cells. The globin portion of hemoglobin is split off and the heme groups of hemoglobin is converted into the pigment bilirubin. Bilirubin is secreted in blood and carried to the liver where it is conjugated with glucuronic acid. Some is secreted in blood and some is excreted in the bile as bile pigments into the small intestines. The presence of trace amounts of bilirubin are abnormal, and require further investigation. Atypical result colors may indicate bile pigment abnormalities. Metabolites of drugs such as Pyridium and Serenium may cause false positives. Ascorbic acid concentrations of 1.42 mIU/L or greater may cause false positives. Causes: liver disorders, cirrhosis, hepatitis, obstruction of bile duct.

Exercise 1: Urinalysis

The goal of the first exercise is to establish your baseline urine composition profile.

- At the start of laboratory, clear your bladder by urinating into a graduated specimen bottle. Record the total volume of urine. Return to lab with at least 50 ml of urine. Dispose of the remainder. Record the time when this collection was made

- Note the total volume of urine collected (in milliliters), the color (light yellow to amber) and transparency (transparent to cloudy).

- Calculate the rate of urine production (ml/min) by dividing the urine volume (ml) by the number of minutes since your last urination.

- Use a pipette (same as above, unless contaminated) to fill a CLEAN, DRY test tube with a sample of your urine.

- Remove a Chemstick from the sealed darkened container. Minimize exposure of these strips to air and light (i.e., seal the container promptly after removing a strip). Do not touch the reagent area of the stick (the colored squares) with your fingers!

- Fully submerge the reagent area of the strip in your urine and immediately remove. The Chemstick should not remain in urine for more than one second. While removing the strip from the test tube, run the edge of the strip against the rim of the container to remove any excess urine.

- Hold the strip in a horizontal position to prevent any of the colors from the test squares from running together and lay the strip on a paper towel to prevent mixing of chemicals.

- Use the indicator key on the Chemstick box to measure the value for each category. All reagent areas should be analyzed/read within two minutes! Record all these values in your laboratory notebook.

- Rinse your test tube, and keep this test tube for future chemstick tests.

- Measure NaCl concentration in your urine: The method we will use measures only Cl- ion concentration, but we will assume that Na+ ion concentration is equal.

- Using a pipet, measure 10 drops of urine in a clean test tube.

- Add one drop of 20% postassium chromate (K2CrO4) solution. The urine sample will turn bright yellow.

- Add 2.9% silver nitrate (AgNO3) solution one drop at a time, and mix the fluid after each drop. Count each drop added. The solution will change brown where the drop of silver nitrate contacts the urine sample, but will return back to yellow after mixing until sufficient amounts of silver nitrate have been added to titrate the Cl- ions, after which time the solution will remain brown. Each drop of silver nitrate added during the titration represents 1.0 g/L NaCl.

Exercise # 2: Effect of fluid intake on kidney function

The goal of this exercise is to examine how urine output and urine chemistry vary with intake of varying ionic strength fluids. Procedure

- For this exercise, you will be assigned to one of 4 treatment groups (Table 1). If you have any medical condition (i.e., kidney dysfunction, hypertension, diabetes) that prohibits you from participating in a particular treatment group, inform your TA.

| Treatment | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Pure Water (hyposmotic) | 7.5 ml / kg body weight |

| Pure Water - double volume | 15 ml / kg body weight |

| Seawater (hyperosmotic) | 7.5 ml / kg body weight |

| Gatorade (isosmotic) | 7.5 ml / kg body weight |

| Coffee (caffeine) | 1 cup |

- Weigh yourself on the scale in the lab, and subtract 5 pounds (for clothing). Determine the appropriate volume you should drink (1kg = 2.2 lbs). Drink the entire volume of your beverage as quickly as possible. Do not ingest any fluids or eat any food for the rest of the laboratory period.

- Record the time you finish drinking your beverage. Collect urine samples at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after ingestion of the treatment. If you need to urinate more frequently, keep a record of the total volume of urine collected during each 60-minute interval. After the 120-minute urine collection, you may eat or drink at will (but outside of the laboratory, please).

- For each urine collection, determine the total volume of urine produced using a graduated specimen cup. Calculate and record your urine production rate.

- For each urine collection, use a fresh Chemstick.to measure urine chemical composition. Also, for each urine collection, determine NaCl content. Record the values for all of the chemstick categories in your notebook.

Data Tabulation

The analyses of the effect of each beverage treatment on urine production and chemical composition will be done using the entire data set from all of the students in the class.

- We will compile a shared table for each individual’s urine data, grouped by treatment. Each student should enter their data for urine volume, production rate, pH, specific gravity, [NaCl], [glucose], and protein for each timepoint (0 @ start of class; and 30, 60, 90 and 120 min post beverage consumption).

Clean Up Your Work Area and wash your specimen cups before you leave!

Things to consider for your Lab Report

INTRODUCTION

Briefly describe the feedback regulation of the human kidney. How could each beverage/treatment potentially affect this feedback regulation loop?

We studied a number of physical, chemical, and biological parameters of human urine. Describe the parameters relevant to this experiment in the context of what they might reveal about kidney regulation.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

How did the results of your Chemstick Tests compare to the normal, expected values? Were any of your test results abnormal? If so, explain (e.g.,: women who are menstruating may test positive for red blood cells in their urine).

How did each treatment affect the results? Think about urine production (volume and overall osmolarity) as well as the time course of the response. How does this correspond to what is known about kidney regulation?

Did specific gravity change over time? If so, in which direction? Explain the results in relation to each treatment.

Which treatment group had the highest average specific gravity? Is this what you would expect? Why or why not?

Which treatment group had the lowest average specific gravity? Is this what you would expect? How can the results be explained?

During the experiment, which group(s) probably had the highest concentration of ADH in their bodies? Which had the least? Explain your answers.

After Lab:

- This will be a group lab report.

- Please divide the work of writing the report by type of regulation, so that each person benefits from the experience of writing the intro, methods, results, and discussion. This will also ensure that the ideas are better connected between sections.

- Please think about effective figures for this interesting lab. Again you should think about interesting questions you can answer with regard to osmoregulation and excretion and design your figures to reveal the answers to them.

- Be sure to brainstorm together now in class

- Please submit a draft for feedback from your TAs

- Please discuss with your lab group before the final draft is submitted.

- In the discussion circle back to the hypothesis and really try to interpret your results in light of muscle physiology mechanisms.

- Please remember to include respective contributions.